Brian R. Hole, President of Willis Lease Finance Corporation, argues there is a compelling case for a sharing economy approach to spare engines where airlines buy fewer spares than needed to satisfy an OEM minimum spare engine ratio, which is a product of the OEM business model. He says the cost savings that an efficient spare engine environment would make for both airlines and the industry in general are difficult to ignore.

A sharing economy is premised on collaborative consumption. The notion that it is far more efficient for a group to consume (or use) an asset than for each member of the group to own their own asset. Think Uber.

In aviation, the spare engine market is ripe for development of these 'sharing economy' efficiencies. Why do airlines need to own and capitalize so many spare engines if they can get a safe, reliable replacement engine from someone else (e.g., the OEM, an MRO, a lessor, etc.) whenever they need it?

This is especially true as engine programs mature, assuming they ultimately operate as reliably as engines like the CFM56 and V2500 have for decades. The economic benefits from adopting sharing economy principles in the spare engine world are real and will ultimately benefit the entire industry if all stakeholders - particularly airlines and OEMs - are willing to buy in.

It is no secret that the engine manufacturer’s business model is like the razor blade business model: sell the shaver at a loss (like new installed engines) and then sell replacement razor blades (read: spare engines and parts) at a huge margin. After spending billions of dollars to develop a new engine and then selling the installs at a loss (or at best a very slim margin), if the OEM doesn’t sell spare engines and parts at a big margin, the business case fails.

OEMs are therefore not only incentivised to sell spare engines, they must sell spare engines in every airline new engine campaign if they wish to provide a competitive offer and still make their business model work. To that end, OEMs conceived the 'minimum spare engine ratio,' which is the ratio of spare engines to installed engines within an airline’s fleet. Historically, OEMs have pushed for airlines to maintain a 10 per cent spare engine ratio, meaning an airline 'needs' to purchase 1 spare engine for every 10 installed engines.

Higher profit margin and more spare engine sales allow the OEM to offer deeper discounts on installed engines and also create a margin of safety against potentially aggressive guarantees and power-by-the-hour contracts, which typically include minimum spare engine requirements. If the airline does not maintain that minimum spare engine cover, it may lose access to those guarantees and PBH benefits. For example, the airline could lose the benefit of an AOG guarantee, through which the OEM guarantees availability of a spare engine if the airline has an aircraft on the ground.

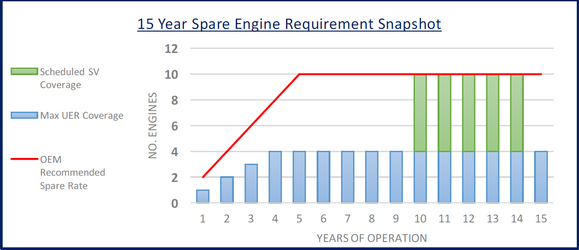

As Figure 1 shows, though, it is incredibly inefficient for an airline to purchase all of the spare engines required to satisfy the OEM minimum. This chart is based on a hypothetical airline (Airline X) taking delivery of 10 Boeing 737NG aircraft (obviously, powered by CFM56-7B engines) per year for 5 years in a row and then operating those aircraft 2,900 hours and 1,600 cycles per year.

The example also assumes Airline X purchases 2 spare engines per year over 5 years to satisfy the OEM’s minimum spare engine ratio. So, by the end of year 5 the airline has a fleet of 50 aircraft (100 installed engines) and 10 spare engines.

The red line in the chart shows the number of spare engines Airline X must purchase to satisfy the 10 per cent spare engine ratio, which requires the airline to carry a whopping 10 spare engines for 11 out of 15 years of operations. The bars in the chart show the number of spare engines Airline X actually needs to support operations, assuming the OEM’s marketed rate of unexpected removals (UERs) for the -7B engine (0.016 removals per 1,000 flight hours) and an average first run of 16,000 cycles before the installed engines begin requiring their first planned overhaul.

Using those assumptions, Airline X only needs about 4 spare engines during the first 10 years of operation – a mere 40 per cent of the number of spare engines Airline X would be required to buy to meet the OEM’s recommended minimum – and then 6 more engines, for only 5 years each, to cover planned maintenance. The gap between the bars and the red line reflects inefficiency and economic waste.

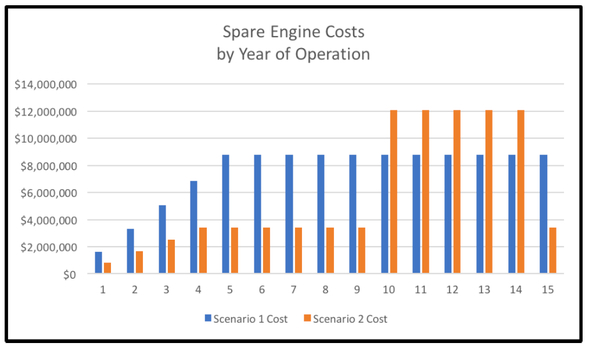

Figure 2 quantifies the value of the inefficiency and the annual cost to airlines of being required to buy too many spare engines. Scenario 1 assumes the airline completes a long-term sale leaseback on each engine it is required to purchase to satisfy the OEM spare engine ratio at an aggressive lease rate factor of 0.63 per cent of the then current list price of the engine per month. In that scenario, the airline will spend nearly US$115 million on rent alone for 10 spare engines over 15 years.

By contrast, in scenario 2, the airline spends just under US$90m if it purchases (and long term finances) only the 4 spare engines needed to protect against UERs and then accesses the short(er) term market to lease the remaining 6 engines needed to support peak maintenance. This is true even assuming those 6, 5-year leases cost over US$120,000 per engine, per month. At US$70,000 rent per engine, per month, the savings produced by scenario 2 over scenario 1 jumps from nearly US$25 million to over US$40 million. That is a lot of money for anyone, but is especially meaningful for airlines that spend their days focused on driving every unnecessary penny of spend out of the system.

Somewhere in between scenarios 1 and 2, Airline X can obtain the same operational security as is provided by the OEM’s recommended spare engine cover without having to buy all of those spare engines. Instead, Airline X could join Willis Lease’s new ConstantAccess guaranteed availability program, for example, which would allow the airline to leverage the dozens of powerplant specialists we employ at Willis Lease and Willis Asset Management to reliably forecast spare engine requirements and then have access, on a guaranteed basis, to our over $1.5 billion portfolio of owned engines to meet those requirements.

We are focused on planning and maximizing utilization of assets by having them in the right place, in the right condition, at the right time for our customers worldwide. If we can guarantee an engine for our customers, why should they be required to buy another spare engine instead? Cost efficiency is our mission and the hypothetical example above demonstrates that airlines can save millions by adopting this approach. The two big questions are: will airlines push for it and will OEMs support it?

There is good reason for OEMs to push back. Increasing efficiencies means OEMs will sell fewer spare engines. But the news is not all bad. Willis Lease will continue to buy more engines to support programs like ConstantThrust and ConstantAccess. In fact, we likely would buy far more spare engines if airlines were buying fewer.

Further, over-sparing the fleet does damage to the OEM business model too. If the OEM sells too many spare engines, those excess spare engines will be unutilized. If unutilized for long enough, rising capital costs will dictate that those spare engines be disassembled for parts. The surplus parts will then compete against new parts the OEMs also count on selling at big margins to support their overall business case. It is difficult to calculate which is worse for the OEM - selling more spare engines, even if some get disassembled prematurely, or selling fewer spare engines and avoiding excess used material. But the cost savings airlines and the industry, generally, would see from a far more efficient spare engine environment should be difficult to ignore.